Jacqueline Saburido has no nose or ears, limited vision, stubs for fingers and constant pain. But she survived the fiery wreck in 1999 that killed two friends on Austin's RM 2222.

Jacqui and her father, Amadeo, have fought hard for little victories that have produced some dramatic gains. In July 2001, their lives were dominated by an exhausting routine of therapies and treatments. She slept with a mask to reduce scarring — some-thing she no longer needs — and her father helped her with stretching exer-cises for her arm before she went to bed.

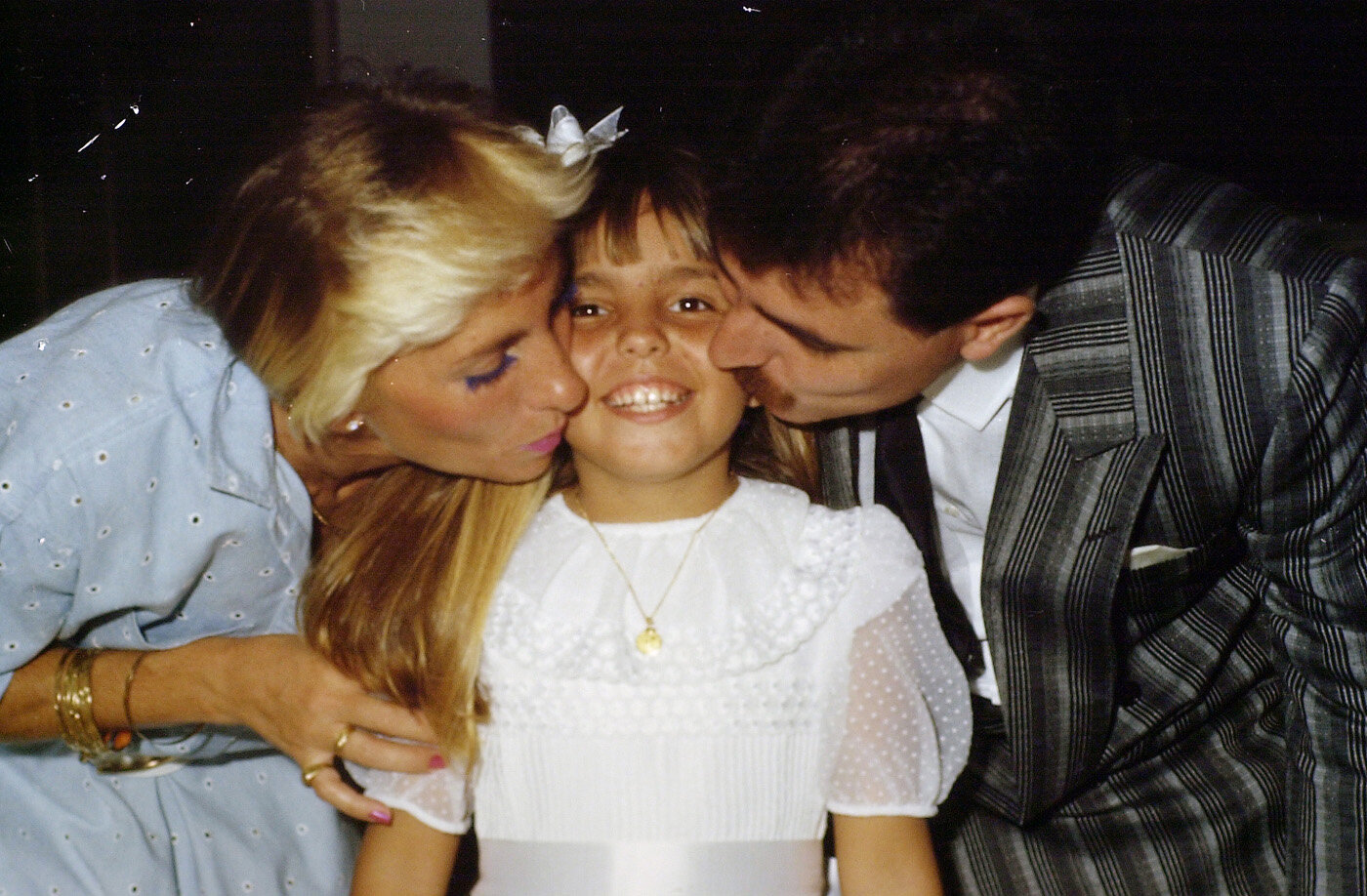

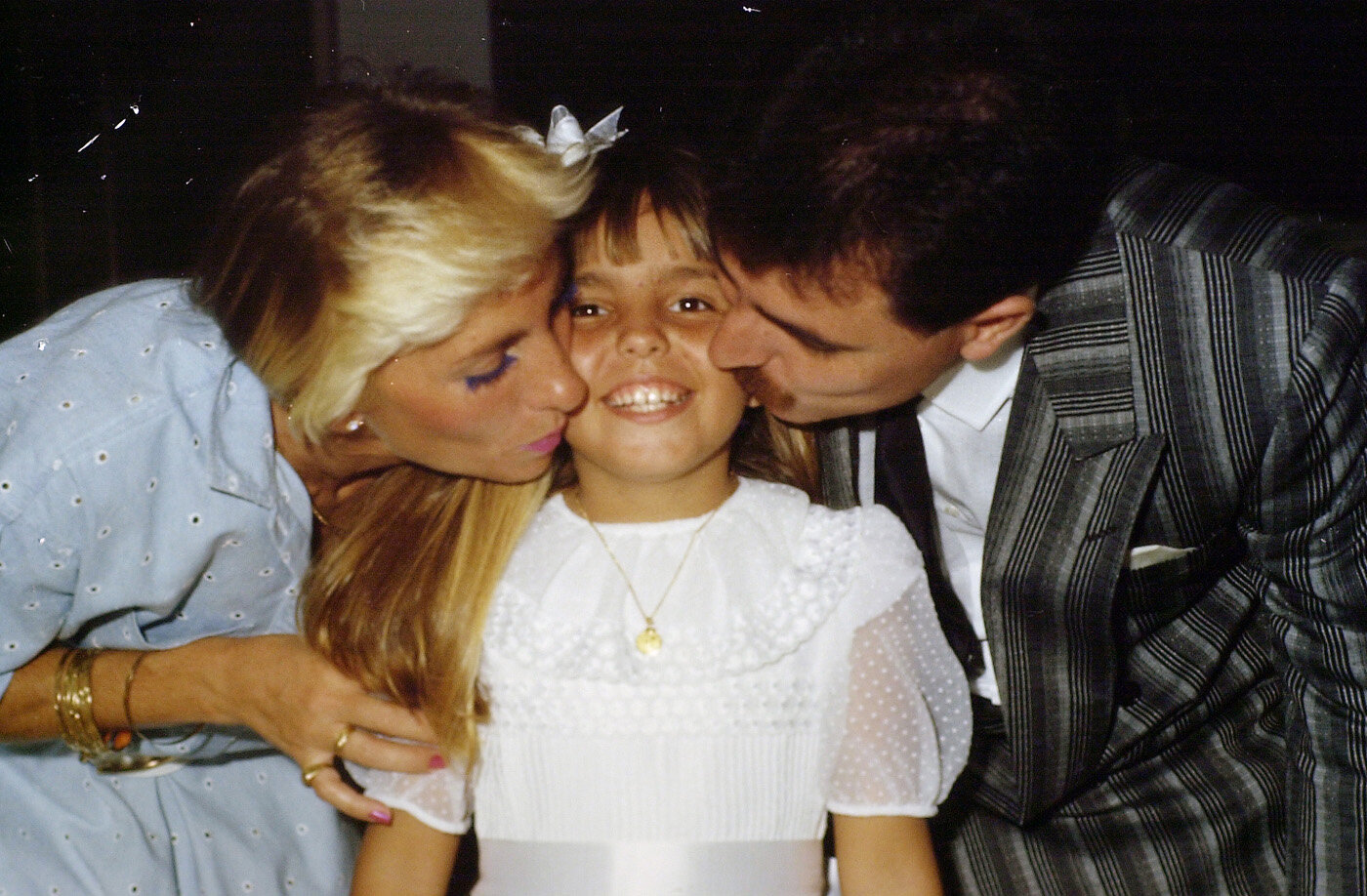

Rosalia and Amadeo doted on Jacqui. Dressed all in white for her first Communion, 'she looked like a princess,' Rosalia remembers. Mother and daughter were and still are perfectionists, arranging them-selves, their clothes and their surroundings just so.

Jacqui no longer has to wear the full-length beige pressure suits that for so long shared her closet with her regular clothes — all neatly arranged. Now she wears only the bottom part of the suits under her clothing.

With a little help from a Velcro splint on her hand, Jacqui could serve herself fettuccine alfredo in the summer of 2001. Whenever she does something new, her father cheers. 'Look, you're eating by yourself,' Amadeo exclaimed one day as he dabbed mayonnaise from around her mouth. 'But you have to wipe my face like a little girl,' she complained.

Jacqui's mother, Rosalia, came to visit in Galveston for a month in June 2001. Jacqui, who jokes that she is more like a child now than she ever was before, has had a sometimes difficult relationship with her mother. After her parents’ separation, 17-year-old Jacqui moved in with her father and ran their penthouse in Caracas.

Children follow Jacqui's every movement as she heads toward her psychologist's office in Galveston before their mother notices and pulls them away. It's a common occurrence, one that Jacqui understands. Back in Venezuela she used to look, too. If she saw someone missing an arm, she looked, even when she knew it made the person uncomfortable. 'I am so curious,' she says.

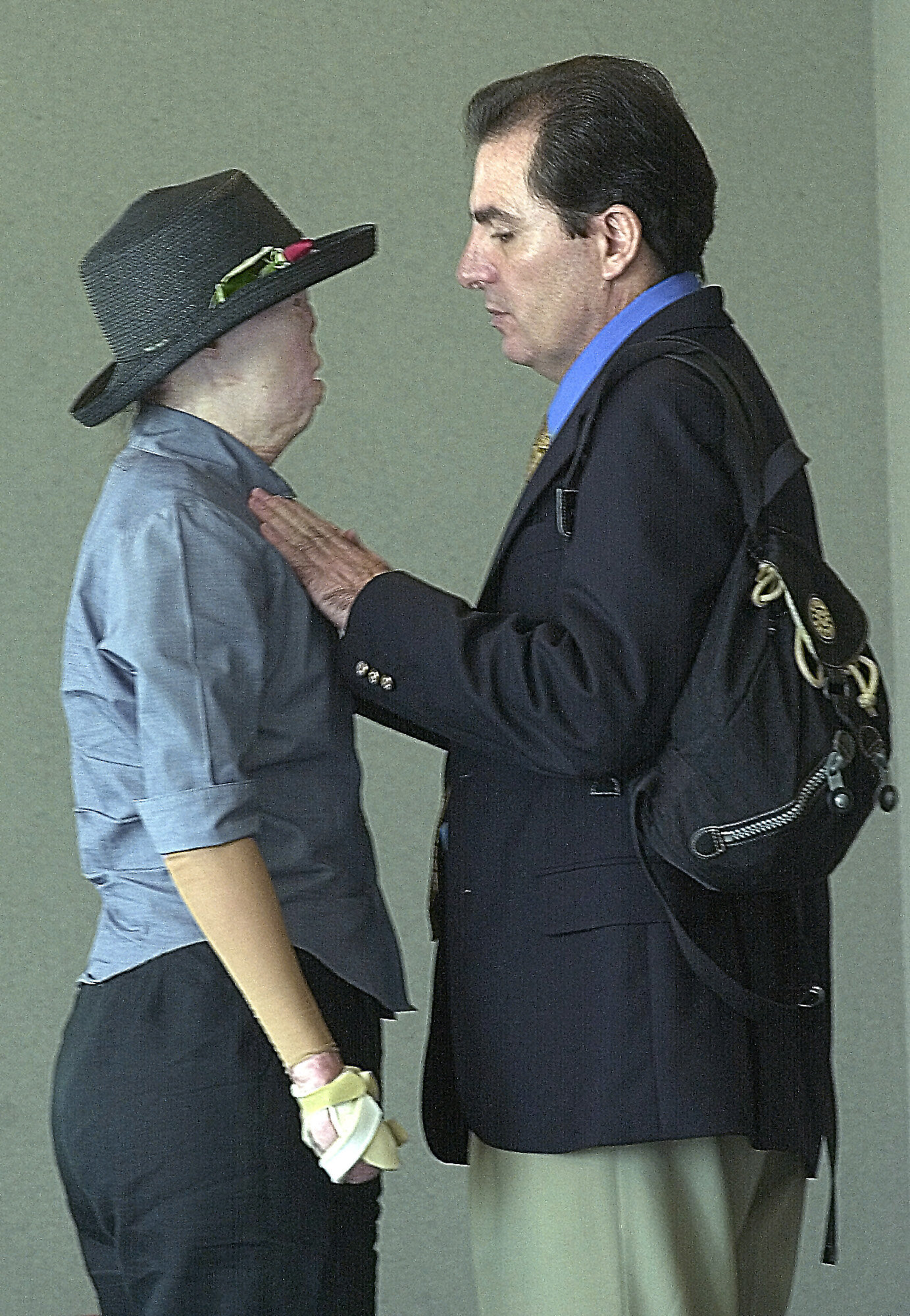

Jacqui loves to have fun, and she's made many friends along the way. One friend from the burn unit in Galveston, Felix Rodriguez, remembers thinking Jacqui was crazy for dancing during therapy. But she inspired him to go forward at a time when he felt like giving up. As they say goodbye after a therapy session in Galveston, Jacqui teases him for putting on weight but admires the dexterity he's achieved with his hands. 'She's got a hellacious attitude,' Felix says. 'She don't let herself give up.

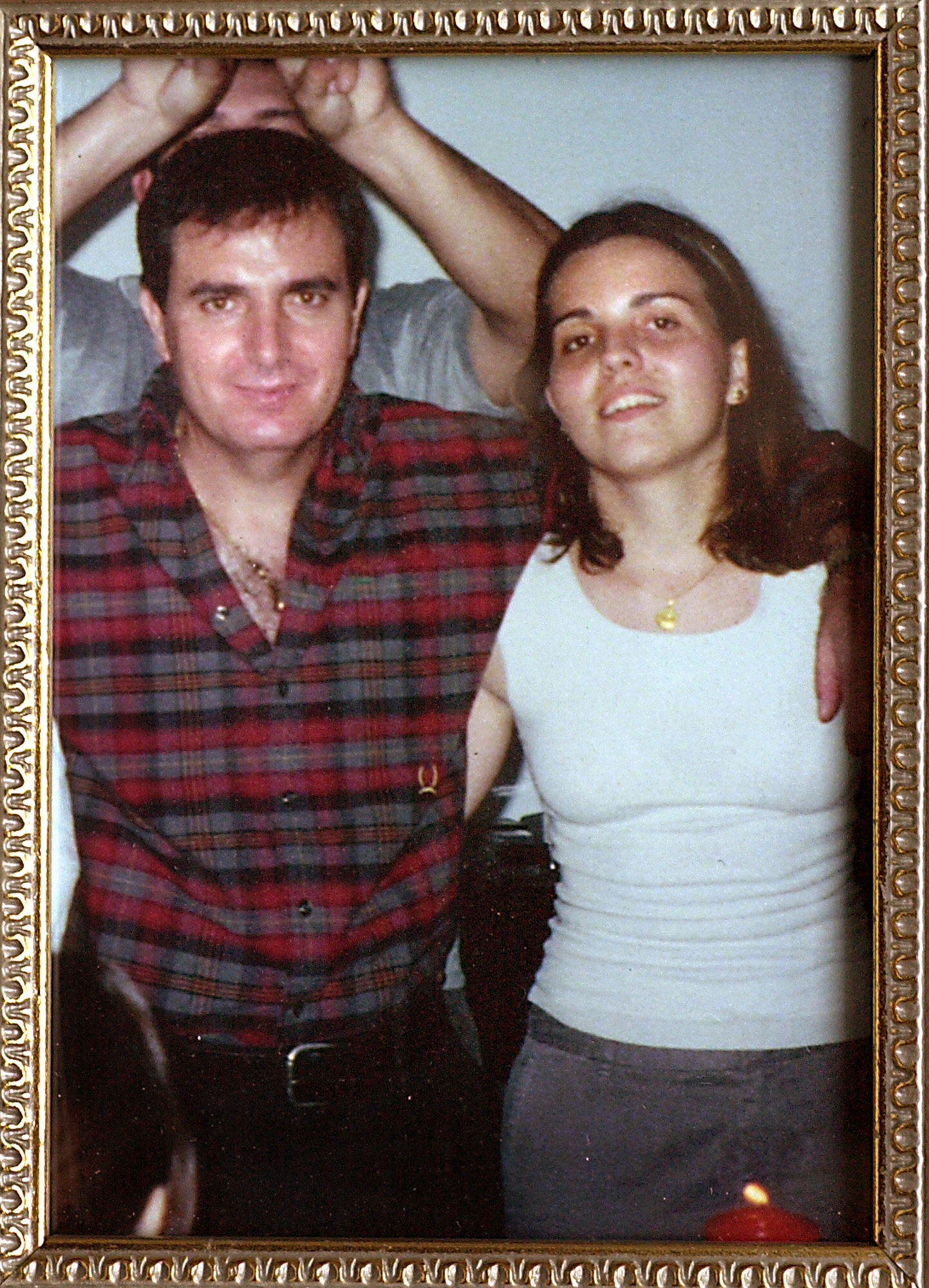

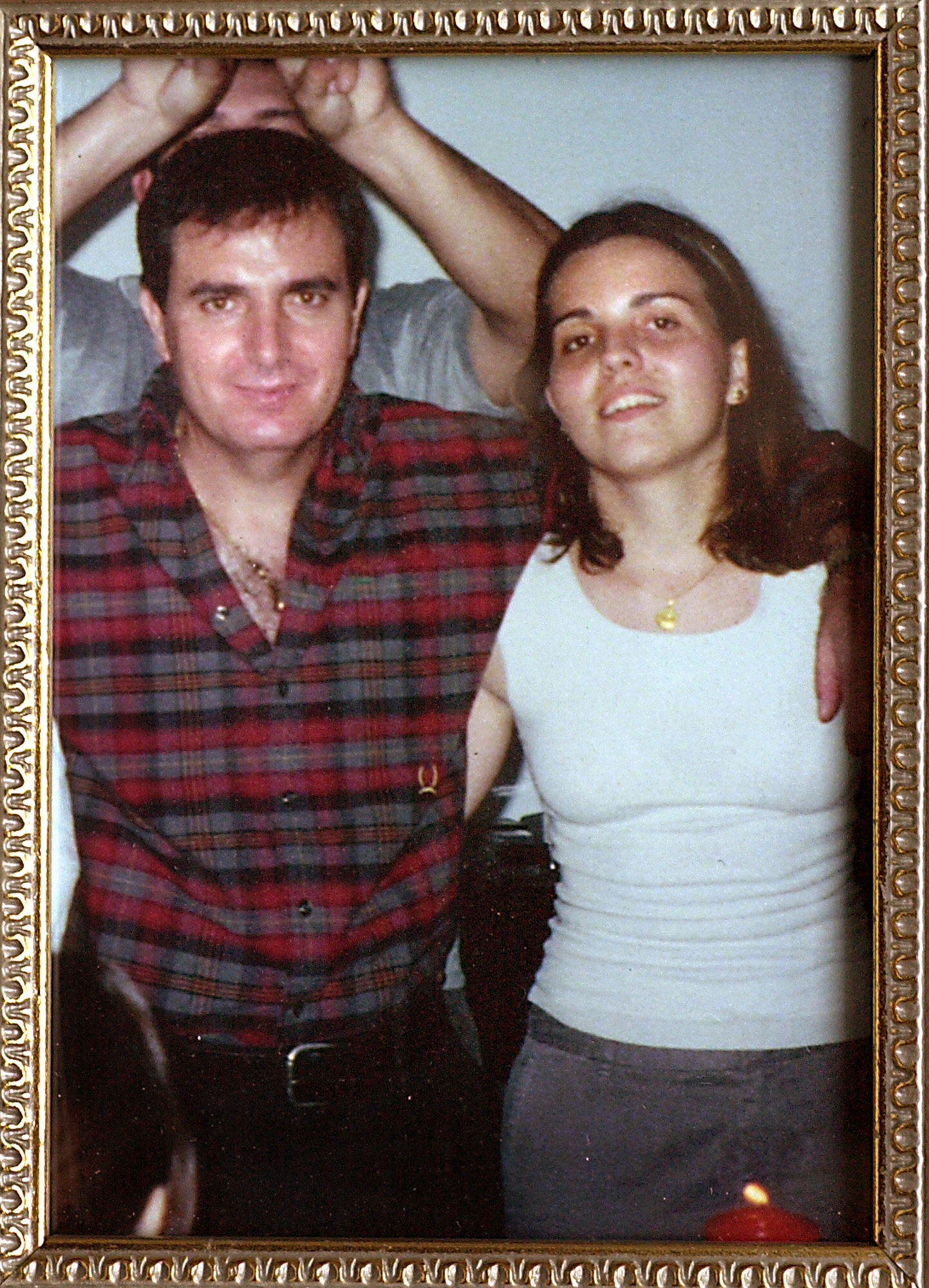

Jacqui displays this photo of her with her father as a memento from her old life. Taken just before she left Venezuela for Austin in 1999, it's a reminder of what she lost, but also of what she still has: her memories and her father.

To help Jacqui navigate her new surroundings, she and Amadeo count the steps at their Louisville apartment complex: 17. They do it together. Although hope sometimes seems to fade amid the grinding daily routine, Amadeo and Jacqui still have hope that Jacqui will recover and be able to care for herself completely.

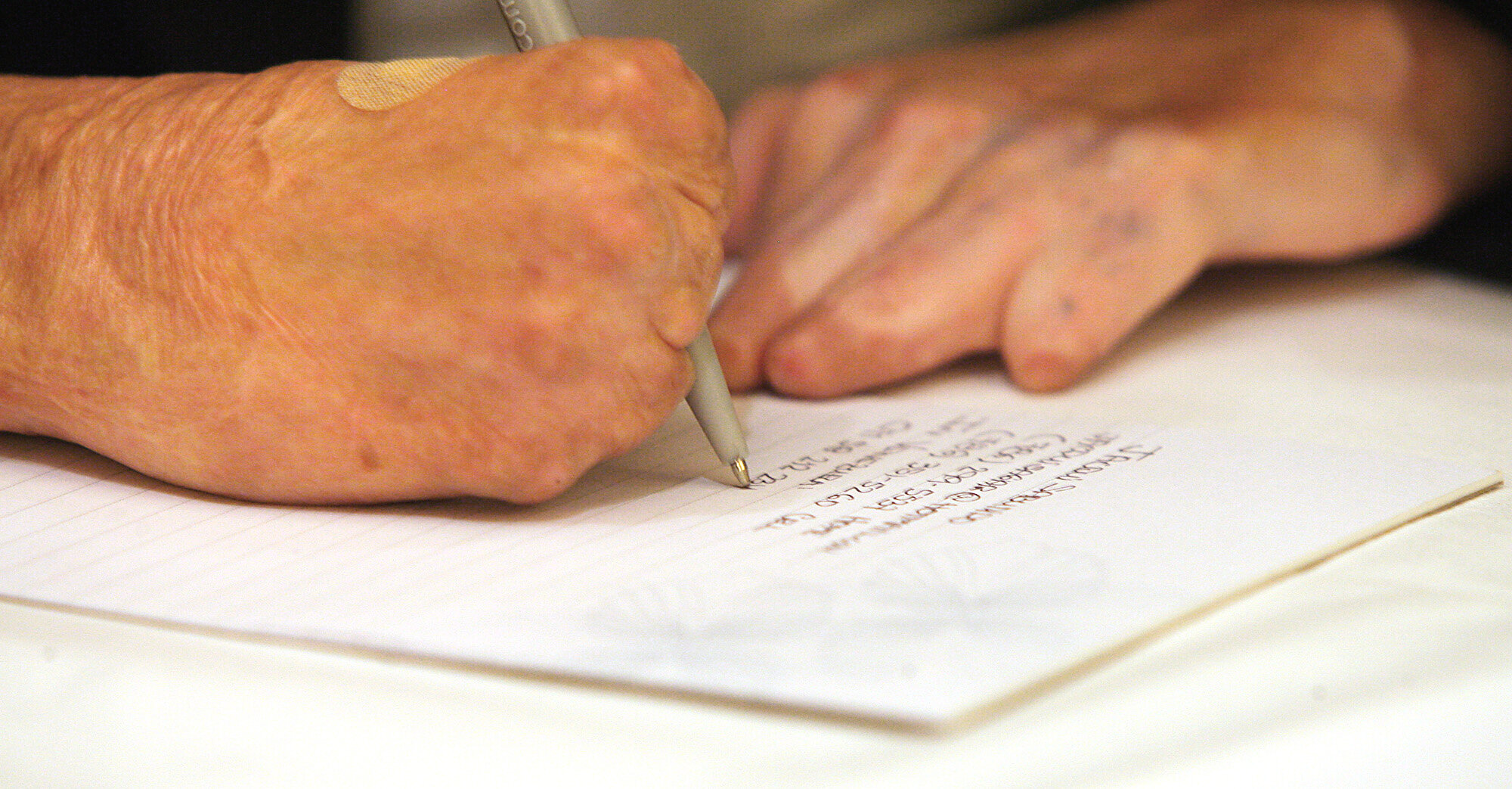

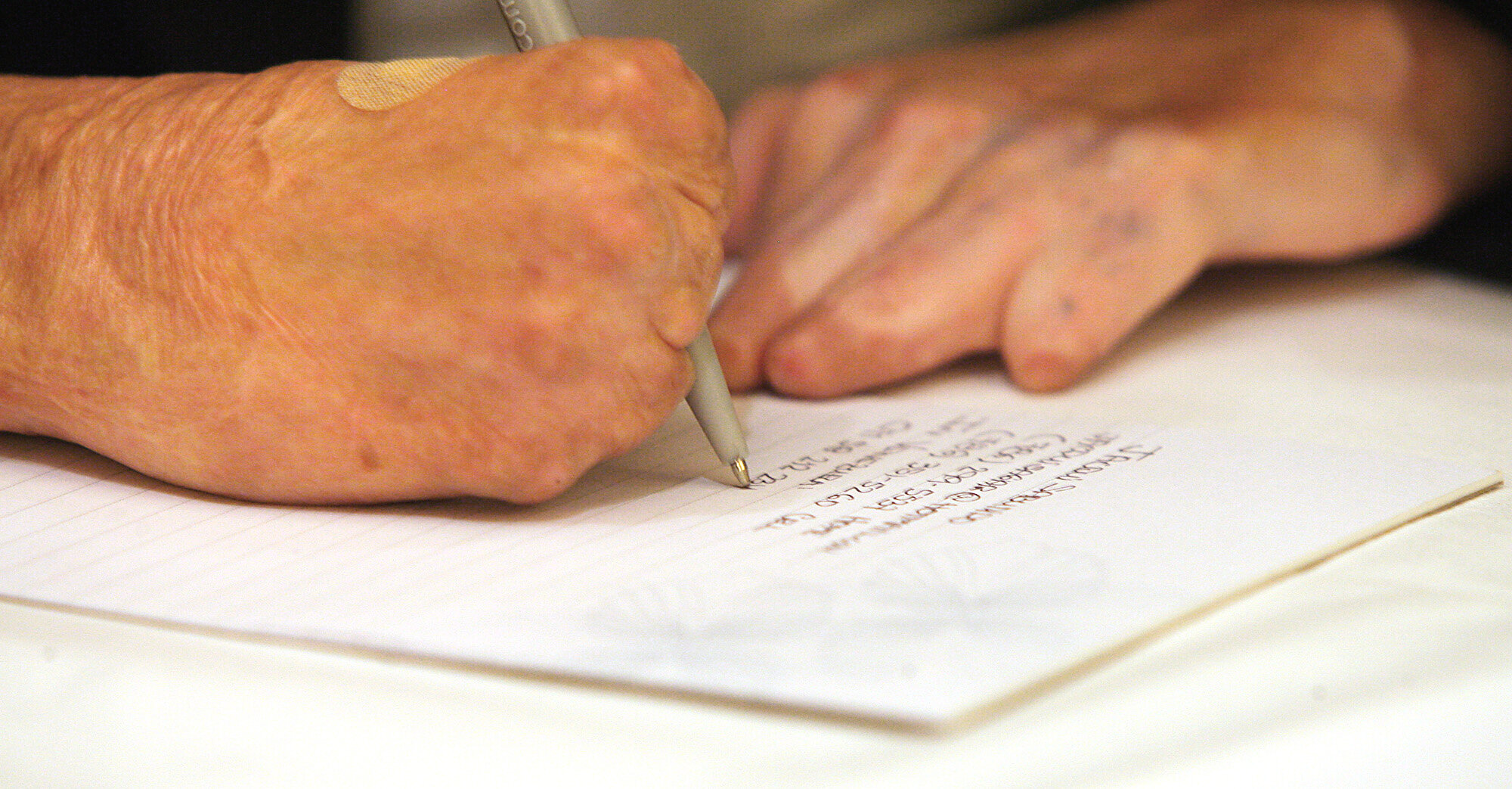

Jaqui’s vision has improved, but last summer, she had to be inches away from the computer screen to read messages. It took her 20 minutes to write a three-paragraph email. Jacqui can’t stand typos. “It takes a lot of patience,’ she says, sighing. “I don’t have a lot of patience.”

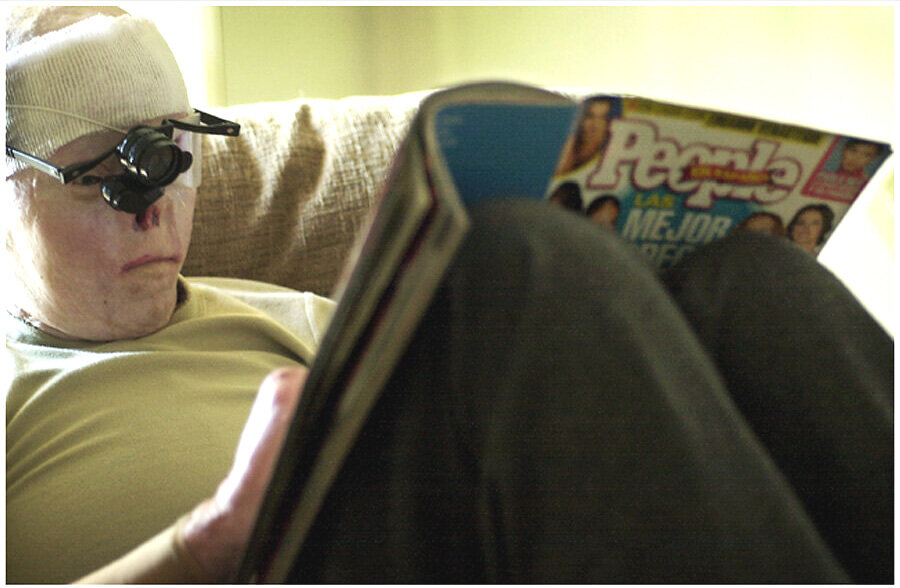

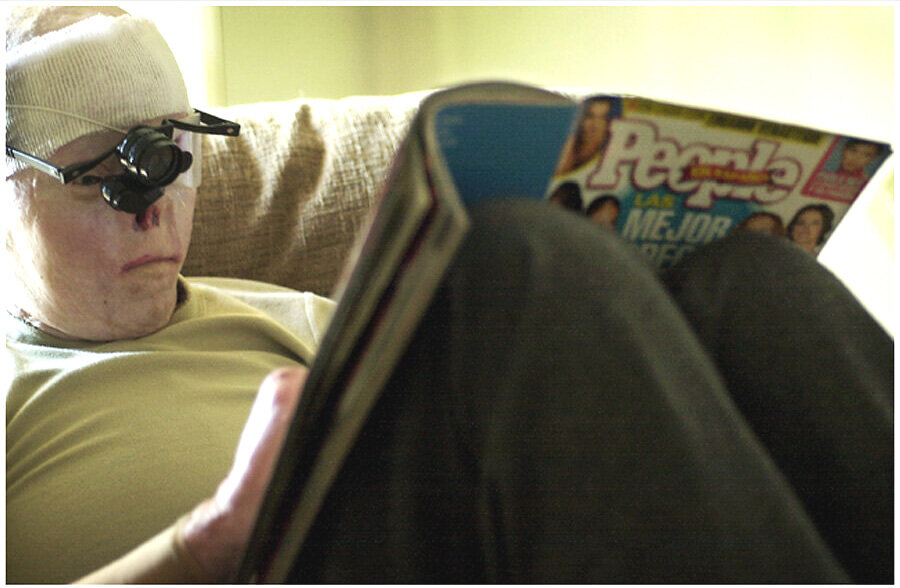

Jacqui favored jeans and light makeup when growing up in Venezuela, a country that turns out vast numbers of beauty queens. She never looked fancy 'but always perfect,' her ex-boyfriend recalls. Jacqui, who's still meticulous about her clothes, checks out a People magazine best- and worst-dressed issue in Louisville in August 2001. It was the first magazine she read by herself, using a magnifying device over her right eye.

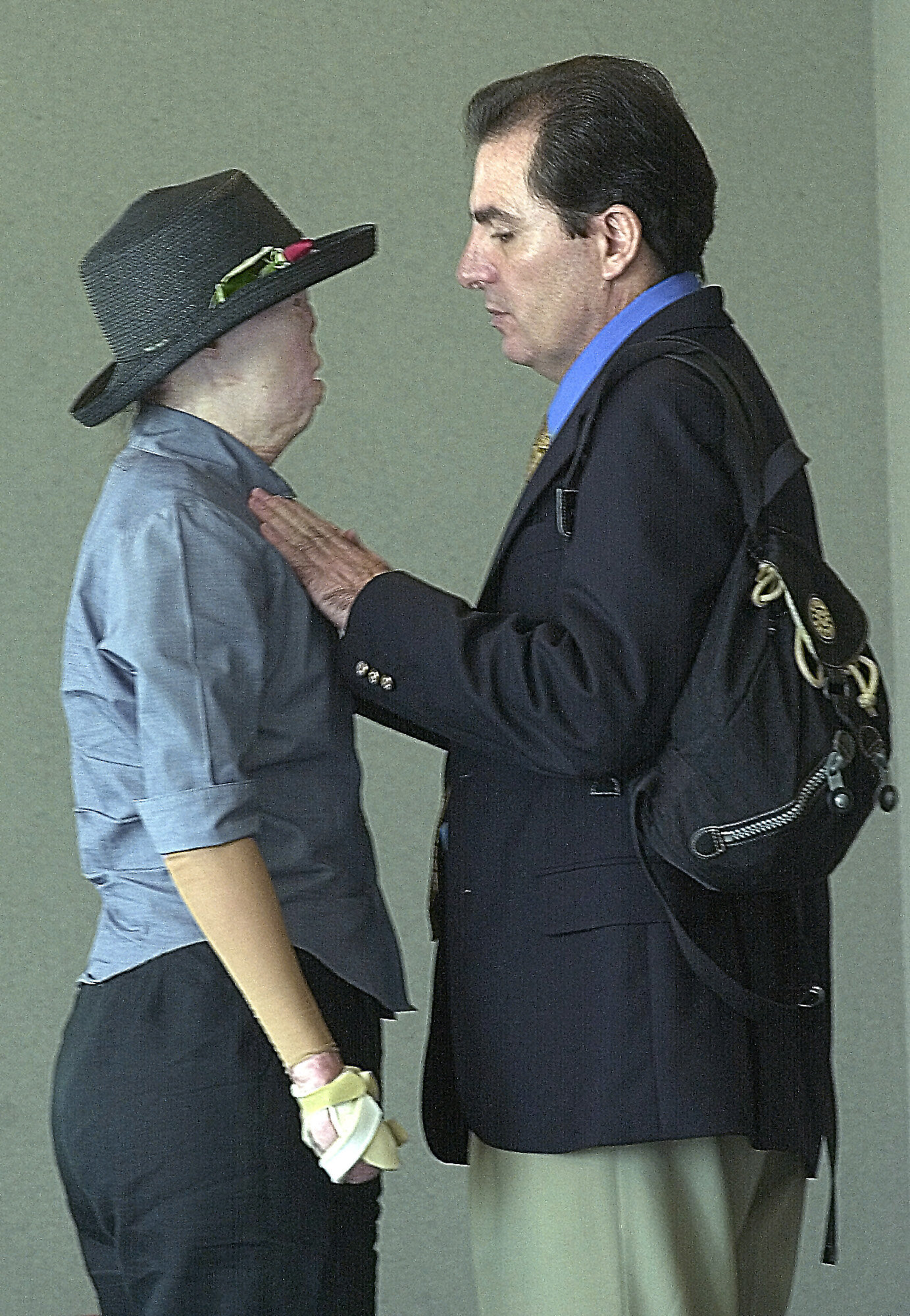

One night in Louisville, Jacqui decides to park the minivan, She can’t do it without help - a devastating realization. Afterward, Amadeo comforts his daughter, ‘It’s not her fault,’ he says. ‘It’s life’s fault.”

One night in Louisville, Jacqui decides to park the minivan, She can’t do it without help - a devastating realization. Afterward, Amadeo comforts his daughter, ‘It’s not her fault,’ he says. ‘It’s life’s fault.”

As another surgeon holds Jacqui's hand, Dr. Luis Scheker threads a needle to attach a skin graft between her fingers. The procedure, one of more than 40 she's had since the crash, was to explore her left elbow for nerve damage and make space between the fingers on her left hand to add dexterity.

Jacqui laughs at her father after he dozed off while waiting for the doctor. Her life is a constant battle against anxiety and depression, but it is a battle in which she comes out on top more often than not. 'What good is it going to do to throw yourself into oblivion?' she asks.

Rescue crews had to use the Jaws of Life to rip apart the Oldsmobile, above, driven by Natalia Chpytchak Bennett, who was killed. Jacqui was in the passenger seat. Laura Guerrero, who also died, was in the back with Johanna Gil and Johan Daal, who were injured.

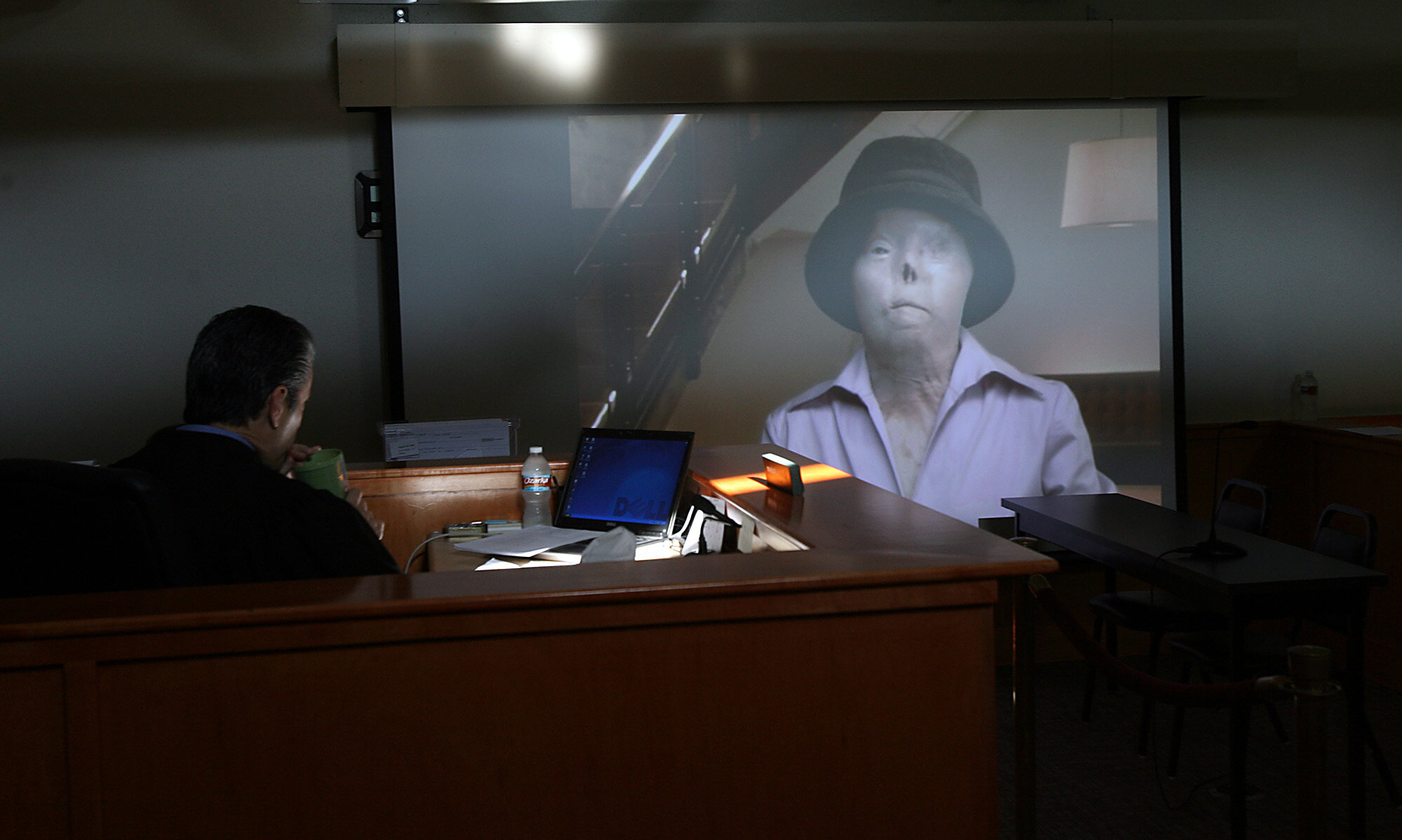

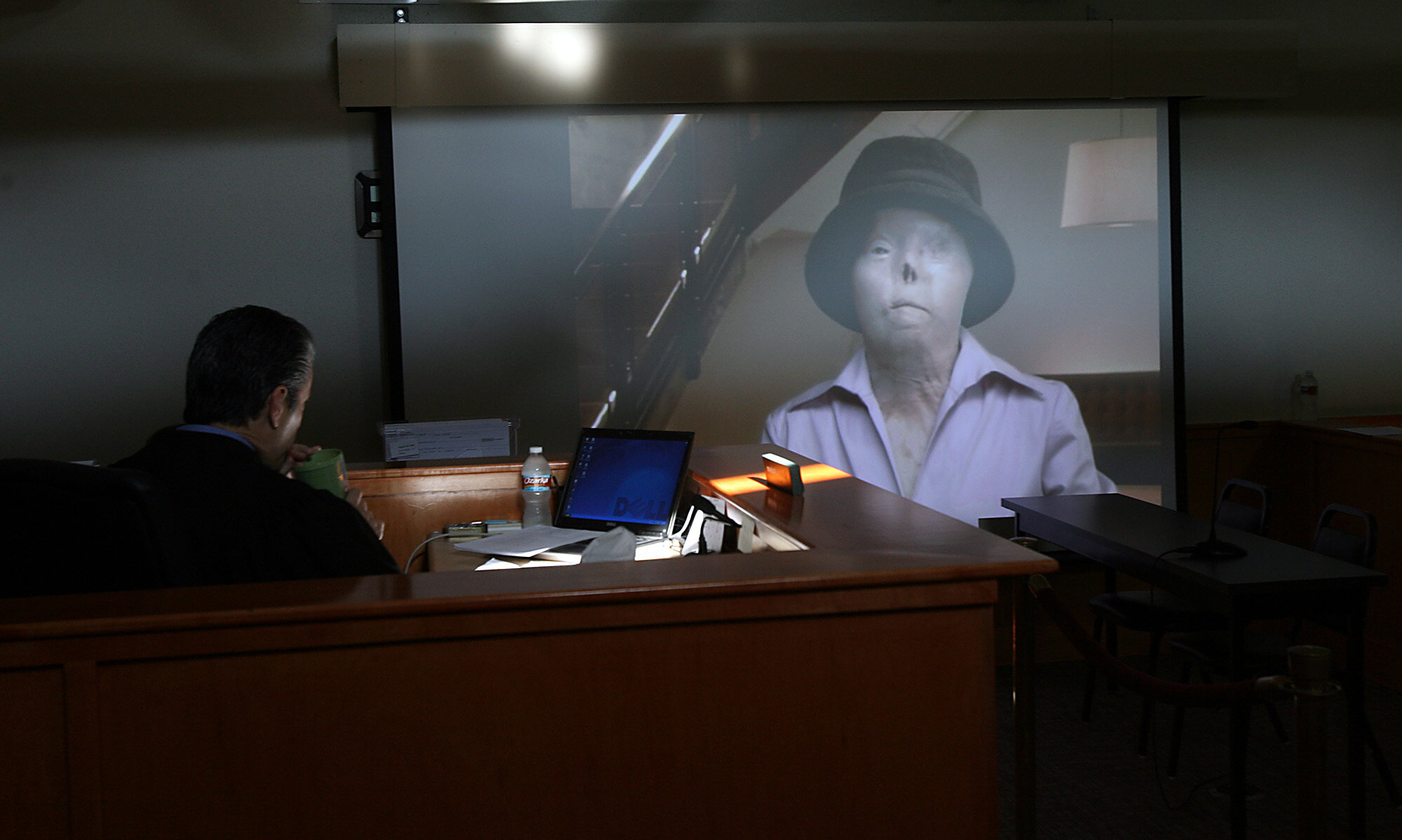

Reggie Stephey, convicted on his 20th birthday of intoxication manslaughter in the deaths of Laura Guerrero and Natalia Chpytchak Bennett, will be eligible for parole in 2005. He and Jacqui appeared in an Austin police anti-drunken-driving video. The damage he did, he says, is ‘a pain that will never go away.’

Posters of Reggie Stephey, and Jacqui Saburido, share a wall, on outside of the Lakeway Municipal Court, hometown of Stephey.

Jacqui Saburido, the face of campaigns against drunken driving, dies at 40

https://www.statesman.com/news/20190422/jacqui-saburido-face-of-campaigns-against-drunken-driving-dies-at-40

Jacqueline Saburido has no nose or ears, limited vision, stubs for fingers and constant pain. But she survived the fiery wreck in 1999 that killed two friends on Austin's RM 2222.

Jacqui and her father, Amadeo, have fought hard for little victories that have produced some dramatic gains. In July 2001, their lives were dominated by an exhausting routine of therapies and treatments. She slept with a mask to reduce scarring — some-thing she no longer needs — and her father helped her with stretching exer-cises for her arm before she went to bed.

Rosalia and Amadeo doted on Jacqui. Dressed all in white for her first Communion, 'she looked like a princess,' Rosalia remembers. Mother and daughter were and still are perfectionists, arranging them-selves, their clothes and their surroundings just so.

Jacqui no longer has to wear the full-length beige pressure suits that for so long shared her closet with her regular clothes — all neatly arranged. Now she wears only the bottom part of the suits under her clothing.

With a little help from a Velcro splint on her hand, Jacqui could serve herself fettuccine alfredo in the summer of 2001. Whenever she does something new, her father cheers. 'Look, you're eating by yourself,' Amadeo exclaimed one day as he dabbed mayonnaise from around her mouth. 'But you have to wipe my face like a little girl,' she complained.

Jacqui's mother, Rosalia, came to visit in Galveston for a month in June 2001. Jacqui, who jokes that she is more like a child now than she ever was before, has had a sometimes difficult relationship with her mother. After her parents’ separation, 17-year-old Jacqui moved in with her father and ran their penthouse in Caracas.

Children follow Jacqui's every movement as she heads toward her psychologist's office in Galveston before their mother notices and pulls them away. It's a common occurrence, one that Jacqui understands. Back in Venezuela she used to look, too. If she saw someone missing an arm, she looked, even when she knew it made the person uncomfortable. 'I am so curious,' she says.

Jacqui loves to have fun, and she's made many friends along the way. One friend from the burn unit in Galveston, Felix Rodriguez, remembers thinking Jacqui was crazy for dancing during therapy. But she inspired him to go forward at a time when he felt like giving up. As they say goodbye after a therapy session in Galveston, Jacqui teases him for putting on weight but admires the dexterity he's achieved with his hands. 'She's got a hellacious attitude,' Felix says. 'She don't let herself give up.

Jacqui displays this photo of her with her father as a memento from her old life. Taken just before she left Venezuela for Austin in 1999, it's a reminder of what she lost, but also of what she still has: her memories and her father.

To help Jacqui navigate her new surroundings, she and Amadeo count the steps at their Louisville apartment complex: 17. They do it together. Although hope sometimes seems to fade amid the grinding daily routine, Amadeo and Jacqui still have hope that Jacqui will recover and be able to care for herself completely.

Jaqui’s vision has improved, but last summer, she had to be inches away from the computer screen to read messages. It took her 20 minutes to write a three-paragraph email. Jacqui can’t stand typos. “It takes a lot of patience,’ she says, sighing. “I don’t have a lot of patience.”

Jacqui favored jeans and light makeup when growing up in Venezuela, a country that turns out vast numbers of beauty queens. She never looked fancy 'but always perfect,' her ex-boyfriend recalls. Jacqui, who's still meticulous about her clothes, checks out a People magazine best- and worst-dressed issue in Louisville in August 2001. It was the first magazine she read by herself, using a magnifying device over her right eye.

One night in Louisville, Jacqui decides to park the minivan, She can’t do it without help - a devastating realization. Afterward, Amadeo comforts his daughter, ‘It’s not her fault,’ he says. ‘It’s life’s fault.”

One night in Louisville, Jacqui decides to park the minivan, She can’t do it without help - a devastating realization. Afterward, Amadeo comforts his daughter, ‘It’s not her fault,’ he says. ‘It’s life’s fault.”

As another surgeon holds Jacqui's hand, Dr. Luis Scheker threads a needle to attach a skin graft between her fingers. The procedure, one of more than 40 she's had since the crash, was to explore her left elbow for nerve damage and make space between the fingers on her left hand to add dexterity.

Jacqui laughs at her father after he dozed off while waiting for the doctor. Her life is a constant battle against anxiety and depression, but it is a battle in which she comes out on top more often than not. 'What good is it going to do to throw yourself into oblivion?' she asks.

Rescue crews had to use the Jaws of Life to rip apart the Oldsmobile, above, driven by Natalia Chpytchak Bennett, who was killed. Jacqui was in the passenger seat. Laura Guerrero, who also died, was in the back with Johanna Gil and Johan Daal, who were injured.

Reggie Stephey, convicted on his 20th birthday of intoxication manslaughter in the deaths of Laura Guerrero and Natalia Chpytchak Bennett, will be eligible for parole in 2005. He and Jacqui appeared in an Austin police anti-drunken-driving video. The damage he did, he says, is ‘a pain that will never go away.’

Posters of Reggie Stephey, and Jacqui Saburido, share a wall, on outside of the Lakeway Municipal Court, hometown of Stephey.

Jacqui Saburido, the face of campaigns against drunken driving, dies at 40

https://www.statesman.com/news/20190422/jacqui-saburido-face-of-campaigns-against-drunken-driving-dies-at-40